Combining pick-by-pick data with advance rate data: when are you drafting a unique roster that is built to win, and when are you just THE PERSON WHO DRAFTED derrius guice?

May 17, 2024

Recently, Underdog Fantasy’s Hayden Winks posted a link that allows anyone to access Pick-by-Pick data from Best Ball Mania IV. Obviously, there’s a lot to unpack here. I’d urge everyone to check out the data in order to:

a) See how many times LeSean McCoy was drafted

b) Gain a better understanding of how the market treated the Underdog player pool in 2023

To try and squeeze more value out of this newly-available information, I combined it with the BBMIV Finals advance rate data. You can still find that here.

I wanted to see if there was any insight to be gained from learning more about building rosters that are good enough to advance through a tournament and also unique enough to potentially win a large-pool contest in a single week (i.e. the Finals).

What I came away with was a newfound understanding of how certain types of players might try to build unique rosters, as well as several reminders that even an efficient market gets things wrong.

BBMIV Roster Spot Breakdown

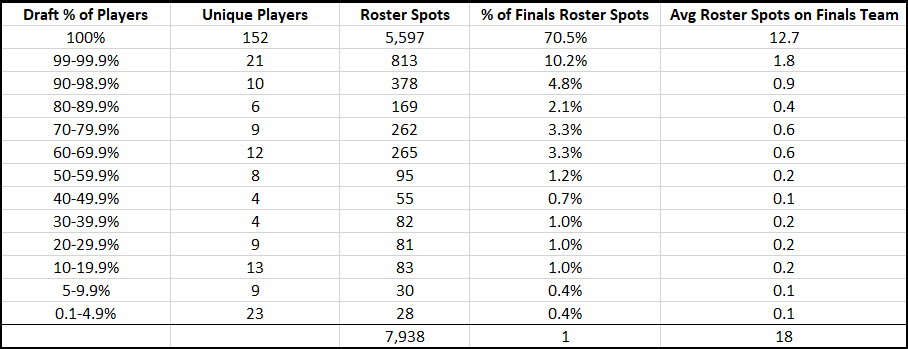

At 441 finals teams and 18 players per team, there were 7,938 roster spots in the BBMIV finals.

Of these 7,938 roster spots, 5,597 (70.5%) were filled by players who were taken in 100% of drafts. This means that, on average, a BBMIV finals team filled roughly 12 of 18 roster spots with players who were taken in every draft room.

The full breakdown:

BBM IV Finals roster spots, broken down by how often these spots were filled by players drafted at certain rates.

The column noting the number of Unique Players in a certain range is included to trigger contextual notes. Your take-away should not be that players taken between 20-39.9% of the time are somehow worth targeting blindly; instead, it should be that the market was unprepared for the performances by Puka Nacua (drafted 31.4% of the time, on 58 finals teams), Baker Mayfield (drafted 22.3% of the time, on 29 finals teams) and Kyren Williams (drafted 19.6% of the time, on 30 finals teams). The actionable advice here would not be “take players the market thinks will be bad in case one ends up being good,” but rather “if you think a player is good or is in a good situation, don’t be scared off by market trends.”

Getting Unique

I also wanted to determine if this data provided any guidance on the best way to build a unique roster. It is objectively true that one of the best ways to gain leverage in a big field tournament (i.e. the BBMIV finals) is to have a relatively unique player or combination of players that comes up big in the week that counts. Having a unique team matters. But what is the most effective way to build a unique team that can actually win? To state the obvious, it’s important to first recognize that a unique lineup doesn’t matter if it doesn’t get you to the finals to begin with. The best ball highways are littered with the corpses of teams hoping for miraculous resurrections of Desean Jackson or Royce Freeman, but when one of these miracles actually happens it can swing an entire contest.

Once again stating the obvious, this is the point where best ball data becomes a bit of a Rorschach test.

As the table above indicates, only 58 BBMIV roster spots were filled by players drafted less than 10% of the time. These 58 spots were filled by 32 unique players. Here is how each performed in Week 17, aka the BBMIV finals:

These players, the ones who were drafted in less than 10% of BBMIV drafts but who were on finals rosters, averaged just under 2.1 half PPR points in the game that counted most. The top performances from this group?

· Trey Palmer – 14.4 points, Week 17 WR 19

· Greg Dortch – 11.7 points, Week 17 WR 27

· Chase Edmonds – 8.1 points, Week 17 RB 31

The max-entry drafters will read this data and say “yeah, that’s the point – look at Trey Palmer” or “yeah, that’s the point – it didn’t happen in 2023, but what if a defender slips in Week 17 of 2024 and one of these low-owned players has a 12-point play?” Neither of these takes is wrong.

It’s also completely ok to be a best ball player who enters fewer drafts and sees this data as evidence that the vast majority of the player selections above were essentially wasted picks. This also isn’t wrong. Having unique players on your roster is not such a significant boost during Weeks 1-16, and if those players don’t produce in Week 17, they likely did not help you much at all.

So what’s the take-away here? This data is probably best used to help you make your own conclusions about unique builds. If you’re a 150-entry player who has 3 Sam Howell stack variations, this data probably tells you to double down on your current, high-risk drafting strategy. You probably shouldn’t keep drafting Derrius Guice, but taking swings on players drafted less often could pay off huge. For high-entry players, this data is also a reminder that most drafts feature most of the same players being taken - championships are decided by either unique combinations or the 3-4 players on a roster that might be atypical.

If you enter, say, 10 drafts, then you’re probably better off judging later round picks not on their chances of making an impact as part of a unique Week 17 roster, but rather on the chance that a specific player might contribute to your advance rate in the first place.

In case you fall into the latter category, the good news is that you still have another option! You can still build unique rosters using ADP trends instead of purposefully drafting higher-risk players. Best Ball Mania II champion Liam Murphy has a fantastic free article on this concept. I’ll leave this one to him – read the article here.

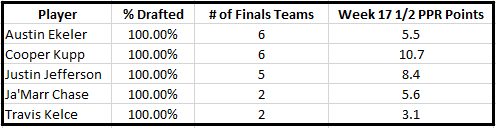

One other note on unique rosters: obviously, the ideal scenario is getting a team through to the finals and having an active player on your roster that was drafted a ton (even 100%), but is on a low percentage of your opponents’ rosters. The most common cause of this is, of course, a star playing getting injured during the season and returning for the fantasy playoffs.

There were a few players for whom this was a possibility in 2023:

Week 17 didn’t go well for these players, and this isn’t a scenario you can plan for. That said, it is a reminder that a unique roster in the finals of a large tournament can often come from random, unexpected circumstances. In other words, the best strategy is probably to just draft the best team you can. There are now relatively proven, effective strategies that can lead to an edge over even a large field, but sometimes the game is just random. In these cases, it’s usually better to have one of just 2 finals teams rostering Ja’Marr Chase than it is to have one of just 2 teams rostering Trent Sherfield.

Conclusions

· While the market is usually very efficient, don’t be scared to invest in players you believe in. A lot of drafters had great seasons last year because they believed in Puka Nacua specifically, and not just “a rookie wide receiver with upside who is only drafted about one third of the time.”

· A unique combination of players who have huge weeks in the finals is the most direct path to winning a tournament. Consider building these unique combinations by going against the ADP grain during various parts of the draft instead of taking wasteful stabs in the final rounds on players who are not only unlikely to produce late in the season, but possibly at any point in the season altogether.

· When determining which drafting strategies to employ, consider all data, but also don’t overthink these drafts. Just draft the best team you can, because you’re probably more likely to benefit from a great roster made unique by random circumstances than you are by building a roster that is intentionally unique.

Always Remember

A player is not good or bad because of where or how often he was drafted. It’s the opposite. He is drafted in a certain spot or at a certain rate because of how the market perceives his future outlook. This is the biggest issue I take with a lot of fantasy football data framing: looking back at players who overperformed or underperformed their ADPs does not help us understand where to look for certain style or performance archetypes going forward in drafts. It only tells us when and how often we were wrong, and it is up to us – the drafters – to understand what led to an incorrect evaluation of a player or his situation. By taking the unique circumstances of each player into account, only then does this – or any other fantasy football data – begin to matter at all.